How my grandparents met: a Yiddish-American romance

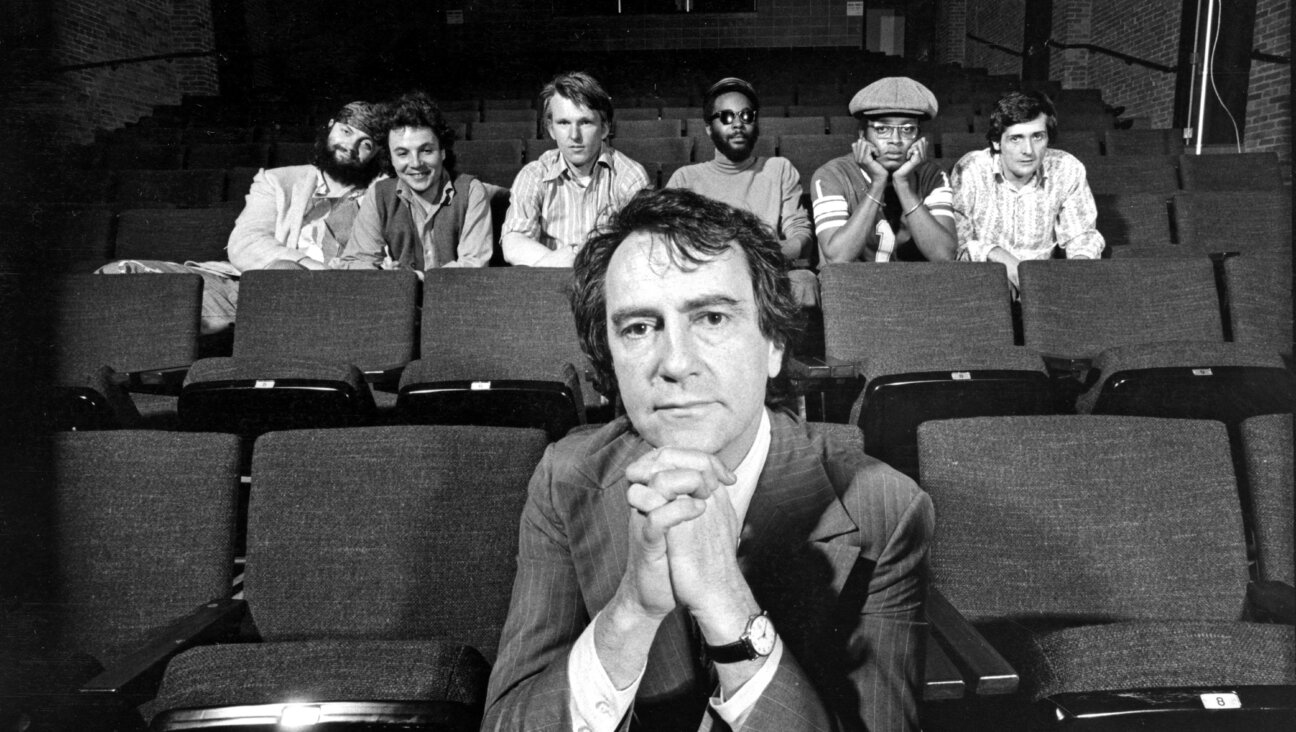

Harry watched, captivated, as Lil spoke to the crowd at a peace demonstration

Lil and Harry as newlyweds, 1940, New Haven, CT Courtesy of the Kaplan family

My grandpa Harry fell in love with my grandma Lil at an anti-war meeting.

As he told the story of their first date years later:

“I asked her: ‘Would you take a walk with me?’ It was in the evening, a pleasant evening. So when we got to the corner of Edgewood Park, I said to her: ‘Would you marry me?’”

That initial proposal didn’t end the way he had hoped.

“Well, I think we’ll have to get better acquainted and take some time to get to know each other better,” she replied.

Harry was handsome and intelligent, but Lil was in no rush. After all, she was a modern woman. She needed time for courtship.

In 1930’s New Haven, their families came from similar origins and were active in the same Yiddish-speaking social clubs: All four of their parents had recently fled shtetls in Vilna Gobernia, Eastern Europe. Harry’s parents were from the shtetl Vasilishki and Lil’s parents — from Kurenets. Both families proudly identified as litvish (Lithuanian) Jews, a group that had a reputation for being intellectual. Though poor, they created a new American home for themselves in a tight-knit, Jewish community.

Harry’s and Lil’s generation bridged the Old World and the new, as first-generation Americans often do. Harry spoke only Yiddish, until he began kindergarten. Because their parents couldn’t use Yiddish as a secret language as other Jewish parents did, they had to use Russian instead. Harry easily learned fluent English, and yet they were striking a delicate balance; they were “proud of their identity,” my uncle told me.

A self-described zaftig woman, with curls that resisted taming, Lil struck Harry as exceptional. He watched her, captivated, as she stood among the demonstrators near Edgewood Park, speaking out for peace. Reeling from the losses of WWI, many Americans were simply too hesitant to enter into another world war. “She had gumption,” my uncle said of his mother.

“And finally,” Harry said, “I was in the audience and I liked the way she was talking about the danger of war. And she was wearing a white blouse and she had pink cheeks. She looked very cute. I liked the way she spoke, so I said to myself, ‘I’ve got to talk to that lady.’”

Weeks later, on a drive with her friends, my grandma suggested: “Maybe we could see if Harry would like to join us.” “Harry?” they asked, incredulous. After all, he was so bookish and introverted. “What did Lil see in him?” they thought.

But Lil insisted. So they drove over to his house, where he was reading. Probably the Scientific American, she thought. “Would you like to go for a ride?” she asked him.

“He dropped the magazine so fast,” she told me years later, laughing. In January 1940, they got married.

They had two weddings: the first, in New York’s City Hall, and the second was a small traditional service, with a chuppah, at Harry’s grandma Tsipe’s insistence.

Years later, I found Harry’s and Lil’s ketubah (wedding contract) in a box in Lil’s apartment. Their Yiddish names and Hebrew dates were on the left side, and English on the right. I deciphered the scribbles and loops in the handwriting in order to find out my grandfather’s Yiddish name. All these years I assumed it was Herschel, because of the initial “H” in Harry. But no, it was Usher, a variation of the Hebrew name Asher.

Their early years of marriage were blissful, until he was drafted. Despite flat feet, advanced age (31) and a pregnant wife, Harry enlisted in the spring of 1943. He served on the front lines for 120 days, including the deadly Battle of the Bulge. At home, Lil and her young child moved in with her parents in their small one-bedroom apartment.

Harry disarmed land mines, witnessing exploded limbs, and lives cut short. “You had to stay calm and have a steady hand,” he explained later. He told me about visiting the Buchenwald concentration camp after it was liberated. He returned home in 1945 to his young wife and first child. Through the GI Bill he could have completed his degree at Yale in just a year or so. Instead, he started working long days at the United Electric Union to support his new family.

Their romance spanned generations. Falling in love in the 1930’s, then the anxiety of the war years, they fell into a daily routine of raising three children on a modest field organizer’s salary. Harry worked hard, taking work calls evenings and even some weekends. Yet that didn’t stop them from going swimming as a family, in Connecticut parks, like Chatfield Hollow State Park or Hammonasset Beach State Park.

Many decades later, deriving naches from six grandchildren, they found harmony aging in their own condo, and later, in a one-bedroom apartment. My grandmother prepared healthy, delicious meals — noodle kugel, or baked chicken, and often cottage cheese for lunch — and my grandfather did the dishes. Every evening they shared a piece of fruit. They loved going for a drive to find local sweet corn in the summer from nearby farms.

Even in their 90’s, they showed each other affection. He would hold her hand, she would kiss his cheek.

One day, after grandpa Harry’s health had declined sharply, our family gathered by his bed. My aunt, cousins, parents and siblings sat there, chatting, and he smiled. “We aren’t rich in money. But we’re rich in grandchildren,” he mused.

When grandpa passed away in the summer of 2006, Lil nearly died of heartbreak. But with the aid of a pacemaker, she lived nine more years, allowing her to dance at two of her grandchildren’s weddings, even to celebrate her 100th birthday. At the party, she was so elated, she danced to calypso music for hours.

At the beginning of the celebration, she approached the microphone and said a couple of words to her guests:

“I was always active, always trying to make things better for people. One of the things I was very strong about was equal justice for women. And that has not even been solved yet because a woman can work with a man, doing the same work, and gets less pay.

“My husband, Harry, could have been a Yale professor, but he chose to be a union organizer. And I was there with him, and I’m proud of him. He’s been gone for so many years, and I can’t forget about him. I dream about him all the time.”

As I became a young adult, Lil and I grew closer. She shared many of her thoughts and feelings with me, and how much she missed grandpa. Their love didn’t end.

“To be with a partner who loves you,” she said, “Oh — that’s a mekhaye, that’s the best.”